Fair warning: considerable spoilers follow – read after watching.

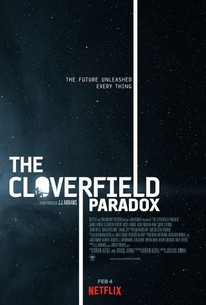

There are any number of angles you could use as an entry point in to discussing The Cloverfield Paradox, the third film in the Cloverfield universe (a term used loosely, the way someone might describe a handful of mismatched dining chairs as a “suite”) that was released on Monday a mere two hours after the premiere of its first trailer during the Superbowl.

Directed by Julius Onah, The Cloverfield Paradox started life as a little film titled God Particle, and follows the crew of a space station – boasting the considerable acting chops of Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Daniel Bruhl, David Oyelowo, Chris O’Dowd, John Ortiz and Zhang Ziyi – using a particle accelerator to perform experiments in renewable energy.

However, one of the experiments goes wrong, kicking off a chain of devastating effects for the crew, while the husband of one of the crew finds that something terrible has arrived back on planet Earth. As a direct sequel to the first Cloverfield, I’m sure I probably don’t need to spell out what that something terrible actually is.

When it comes to this film, you could talk about the release strategy – you could actually write at length about how revolutionary Netflix is for purchasing this film, then holding back any information about it, then premiering a trailer and releasing the film on the same day. And it is a ballsy move, one that should surely terrify traditional theatre chains.

In fact, I’d argue that – regardless of how good or bad the film might be – this was the perfect film to try this out with: a mid-level budget sci-fi with a better-than-needed cast that ties into an established franchise. I don’t know if this was the right way to release a film on Netflix, but I was very excited when it happened.

The other effect here is that it renders critics completely irrelevant. The role of critics in a film release is simple: critics attend preview screenings then they (and by extension aggregator sites like Rotten Tomatoes) provide an opinion on a film ahead of release that gives an idea of the collective thought on any title. Occasionally they can’t do this because critics are held back from viewing a film until release, which generally indicates that the film is not good.

By releasing the film the same day they announce the film, Netflix has bypassed both these stages and made the critical response irrelevant. Most viewers would have no idea going in that the film has a 19% critic score on RottenTomatoes.

If release strategies bore you, you could talk about the notion of requisitioning an existing film and adjusting it to fit something else, even if the original property doesn’t necessarily fit what you’re already trying to do.

As you watch The Cloverfield Paradox, it becomes clear that you’re watching two movies: one that was made before it was added to the Cloverfield line-up and one that was made after, with the space station stuff part of the former, and a few wedged-in references to the name – plus the handful of scenes on Earth – firmly part of the latter.

I’ve talked at length about franchise film-making in the past; this is most definitely not the way to go about it.

Look, if you’re talking interconnectivity, the best franchises are those that are planned well in advance. Look at the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or the Star Wars universe, both of which are meticulously planned so that they make collective narrative sense. Or look at something like the Fast & Furious franchise, or even the Die Hard franchise. You don’t see the best buying finished (or half-finished) films and forcing them to fit a larger picture. Franchise films must be made to fit from Day 1.

If franchising bores you, you could discuss the cast. This is a very strong ensemble: Bruhl continues to impress, even though he didn’t have much to work with here, and Mbatha-Raw is an absolute star deserving of far more leading roles than she is getting offered. O’Dowd provides some much needed – albeit fairly wooden – comedic levity. And a later appearance by Elizabeth Debicki provides a spark that lights up the back half of the film.

You could even talk about the story. The Cloverfield Paradox purposely leaves us with a vague ending that ties back in to the start of this franchise, giving viewers the opportunity to spend their post-film time discussing what the ending means, how exactly this film fits, where in the timeline this film fits, what caused the events of the first film … a dozen discussion threads on Reddit are testament to the fact that this is already happening.

The Cloverfield Paradox provides so many talking points that it is easy to overlook one thing that not many are talking about: guys, the film just isn’t that good. The release strategy excites me, and I love the cast, but it’s all in service of a story that makes little sense and – worse – doesn’t really offer anything unique; it’s a kind of hodge-podge of outtakes from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Event Horizon and Aliens, with visual cues from Alien, Gravity and Mission To Mars.

To borrow a phrase I read over the weekend: as a new way of bringing content to audiences, The Cloverfield Paradox is an interesting experiment in release strategy – and as an engrossing and entertaining sci-fi film, The Cloverfield Paradox is an interesting experiment in release strategy.

The Cloverfield Paradox is directed by Julius Onah, from a script by Oren Uziel and Doug Jung, and stars Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Daniel Bruhl, David Oyelowo, Elizabeth Debicki, Zhang Ziyi, Chris O’Dowd, John Ortiz and Aksel Hennie. It is available worldwide on Netflix now.